Longtime Slots Lover Doesn't Like the Action in Maryland

Slots have been very good to William "Whitey" Roberts. Back in the 1950s and '60s, when Route 301 in Charles County was the Vegas of the East, when Sinatra and Dolly Parton and Guy Lombardo performed at places such as the Stardust, the Wigwam and the Waldorf, Roberts was the guy who knew and nursed the machines, the engine of the Sin Strip.

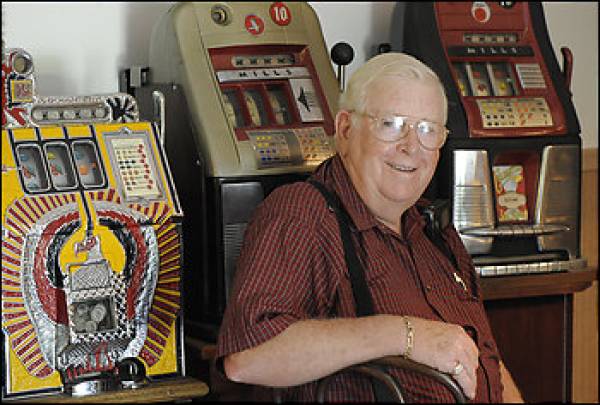

He's at it still today, at 75, in retirement at home in Waldorf. His basement is a showcase of vintage mechanical slot machines, each lovingly restored to one-armed-bandit glory by one of the last craftsmen in the country who can re-create the sweet whirrs and clanks of three cherries spinning into the display window, that magical moment when the coins shower into the waiting palms of a lucky gambler.

In Roberts's time-sweetened memory, slots were a powerhouse of profits, fun and jobs, an economic boon to a place that had previously struggled to get by on tobacco and wheat. Where big-box retailers stand today, motels, restaurants and bars catered to the joy-seekers of the East Coast, travelers in search of instant cash and all the gaudy stuff that comes with it.

In his basement, Roberts has restored to working order the Bursting Cherry, the Rol-A-Top, the High Top and other classic machines that collected gamblers' coins until the state banned slots in 1968. If you pull the lever just right, and you know the machine the way a safecracker knows his prey, you can pretty well assure yourself of winning a $7.50 jackpot.

But much as he loves those machines, and much as he believes slots brought little but good to the people of Southern Maryland until government stepped in to kill the fun, Roberts has decided that he cannot support Gov. Martin O'Malley's push for legalized slots gambling.

The governor contends that after a three-year setup phase, slots would generate more than $600 million a year, about half of which would go to schools. About $100 million of slots revenue would subsidize purses for horse races. Opponents of slots say the state's revenue estimates don't account for the downturn of the economy. In addition, they say, the money that would go to schools would not be additional dollars, but instead would free up state funds now spent on education so that money could be spent on other programs.

Roberts and his wife travel out of state to enjoy gambling, but he says he'll vote next month to keep slots out of Maryland, largely because the current proposal uses slots profits to subsidize the horse industry.

"I love slots, but it has to be honest," he says. "This is a farce. To take the money from slots and just spread it around the state government isn't being straight. They say the money goes for schools, but it's also going for everything else the state does, and a whole lot of it is going to the horse industry. If horse racing can't sustain itself, it should be gone. If I had a shoe shop here and I was failing, they wouldn't carve out a piece of the slots for me."

Along Route 301 today, many of the old slots spots are gone. The Waldorf restaurant, which Roberts managed for many years, has a different name, but the motel is still open and his wife still works there. The surviving buildings from the slots era, sprawling two-story motels from the Howard Johnson's school of architecture, linger in drearily deteriorating condition, awaiting a real estate developer's golden touch. The wooden teepee of the Wigwam stands, though it is camouflaged by trees and ivy intent on taking over the abandoned building.

Four decades ago, on the road between La Plata and Waldorf, writes Bob "Dex" Armstrong, who came to know the strip as a torpedoman at the naval base in Norfolk, "you could lose your money, your virginity, get your car painted, your fanny tattooed, [be] photographed with women your mother wouldn't approve of, buy every type of illegal fireworks, firearms, booze [and] plaster lawn ornaments, meet motorcycle bad guys, and use restrooms a self-respecting pier rat wouldn't enter."

A 1950s magazine called Man's Conquest touted the 301 strip as "felony row," and a Maryland grand jury in 1962 blamed slots for turning Southern Maryland into a "sordid mess," where teenagers played the machines, owners failed to report profits and elected officials looked the other way. Or worse: Politicians routinely worked directly for the slots rooms, managing the action or distributing the machines.

That's not how Roberts remembers those days, but he knows how desperate the hotel owners were to hold on to the machines. When the state forced operators to start phasing out the slots, limiting each venue to 20 machines and then, a year later, to 10, the owners prevailed upon Roberts to create a mechanism that allowed 10 players at a time to play a single machine.

Finally, in 1969, when slots were totally illegal, hotel owners came up with one last effort to save gambling, allowing players to compete for merchandise rather than cash. Winners could walk away with anything from a transistor radio to a diamond ring. It took the state a year to rewrite the law to shut down those games, too.

"As soon as all that was gone," Roberts says, "the government went into the numbers racket. They started with the lottery, and now there's the scratch-off cards and the keno. The government now controls everything the mob used to control. Everything that was so bad for us -- the numbers, the slot machines -- everything that they shut down because they said it was hurting the poor people, is now perfectly okay because it's run by the government. Sorry, I'm not buying it."

----

Marc Fisher, Washington Post