Bookies Behaving Badly Part 5: Shill Edition

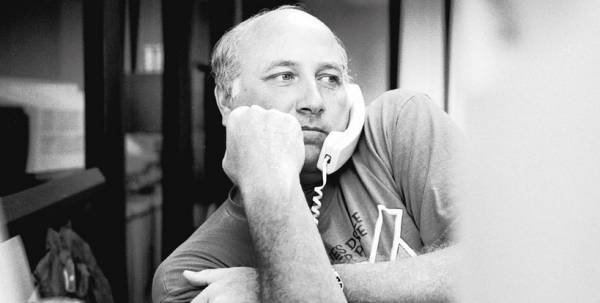

When it comes to bookies behaving badly, few were as slimy or sleazy as the one nicknamed "The Shill"--Steve Schillinger.

The nickname was of twofold origin--"Shill" of course was short for Schillinger and was a nickname since youth, but shill is what he did as a bookie and so became just as relevant.

Schillinger grew up in the Chicago area in the 1950s, listening to a popular local AM radio station with the call letters WSEX.

He'd never get those letters out of his head.

After college, he found himself in San Francisco working as a stock broker at the Pacific Exchange, one of many minor stock exchanges around the nation.

But he also had another, more lucrative job as he toiled in the pits of the Exchange trading shares of stock--he was the workplace bookie.

In between buying and selling shares of IBM, Xerox and AT&T for clients, he was booking bets on the San Francisco 49ers, Golden State Warriors and Oakland A's for his co-workers.

He was doing well--he lived in a ritzy Frisco suburb and drove a pricey red sports car that would have any midlife crisis-sufferer drooling with envy.

Then the bottom fell out in 1996, and it wouldn't be the last time it would happen.

One of Schillinger's fellow stock brokers at the Pacific Exchange had a particularly brutal Sunday betting NFL games with "The Shill" and had lost a lot of money.

A lot as in five figures a lot.

And a lot as in he didn't have the money to pay Schillinger.

When the losing bettor told his parents about his predicament, in an effort to get a loan from them to pay "The Shill," the parents complained to the head of the Pacific Exchange and Schillinger was immediately fired.

Schillinger then left the Exchange and stiffed out of thousands of dollars all of his betting customers who had won that week.

The experience of getting caught and canned for bookmaking didn't leave much of a sour taste in Schillinger's mouth, though--he was off to tropicial paradise to do it again.

But in a much bigger way this time.

The year was 1997 and a new invention called the Internet was just starting to explode in popularity.

One of the engines driving that popularity was the myriad ways the Internet could be used--new ways were being developed every day it seemed.

Schillinger had an idea--why not mix his lifelong love of sports betting and booking sports wagers with this new technology called the 'Net?

And that's just he did, creating the world's first Internet sports betting site, called the World Sports Exchange, or WSEX for short.

The site was modeled after a stock exchange, meaning you could buy shares in a team while a game was in progress, with the value of the shares increasing or decreasing depending on that team's fortunes in the game.

You could also make traditional sports bets on teams in all the major pro and college sports.

Schillinger set up shop in the twin island Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda.

He convinced two of his pals from the Pacific Exchange--Jay Cohen and Haden Ware--to join him in perpetual 85-degree weather at WSEX headquarters in St. John's, the country's capital and largest city.

Cohen was a scrawny but brilliant computer geek from New York who went to college at the University of California at Berkeley, fell in love with the Bay Area and also got a job as a stock broker at the Pacific Exchange.

Ware was a wannabe broker from Boston who worked at the Exchange as a gofer for Schillinger and Cohen, getting them sandwiches and coffee and performing other menial tasks.

After a rocky start, WSEX started to take off in popularity as the site gained publicity.

Schillinger and Cohen did numerous interviews on radio and TV and with magazines and newspapers about their enterprise, and lots of new customers were signing up--and losing their shirts, as most sports bettors do.

"Shill" & Company were getting rich.

The hell with a sports car!

After one particularly huge win for WSEX, on a Monday Night Football game, Schillinger bought himself a yacht.

It was high times in jolly ol' St. John's for the WSEX trio, and the best thing about it (after the money), Schillinger told Morley Safer of CBS News during an interview with the TV show "Sixty Minutes," was that, "I don't have to wear shoes to work."

Then Cohen went off the reservation.

Up to that point, all media interviews given by Schillinger and Cohen (no once cared about Ware) were about promoting WSEX and why America should sign up immediately and start betting on sporting events via the Internet.

But then, in 1998, for no apparent reason and to this day still a major mystery, Cohen did an interview with the sports magazine Sports Illustrated and stuck a finger in the eye of Uncle Sam.

Instead of just promoting WSEX in the S.I. article, which he did with gusto, Cohen, knowing his company was of questionable legality at best, basically challenged the U.S. government to come after him and WSEX if the Feds thought what they were doing was illegal.

And come after them they did.

Just a few weeks later, in the first Federal prosecution of offshore Internet bookmakers--the so-called "Internet 21" case--then-Attorney General Janet Reno announced Federal charges against 21 Americans who were running or helping run bookmaking operations in the Caribbean and Central America that took sports bets via the Internet and/or telephone.

Schillinger, Cohen and Ware were among the unlucky 21.

Cohen returned to the USA to fight the charges and famously went on trial, lost and served a year and a half in Federal prison, while "The Shill" and Ware remained in Antigua without missing a beat, continuing to run WSEX.

Cohen, against the orders of the court, rejoined them in Antigua after he got of the slammer.

A new century was upon us and WSEX continued to thrive.

And then all of a sudden it didn't.

Reports began surfacing, slowly at first and then with an onslaught, that WSEX wasn't paying its winners any more.

"Steve the Shill" was now "Steve the Stiff."

It didn't surprise anyone back in San Francisco who knew Schillinger back in the day at the Pacific Exchange--they had seen his cheating ways.

In fact, it shouldn't have surprised anyone--media outlets from the Las Vegas Sporting News to ESPN had reported on WSEX and Schillinger's tendency to lie, cheat and steal from his customers back in his Exchange days.

It was only a matter of time before he'd repeat the behavior at WSEX, and repeat it he did.

So greedy had he, as well as Cohen and Ware, become that they were no longer content with the millions of dollars in profits they were making booking bets on the Internet.

They wanted more--we want "billions with a b, not millions with an m" Cohen famously declared in one interview--and the quickest way to get it was to steal it.

From the customers.

As in, just don't pay them.

Any of them.

Ever again.

So that's what WSEX did.

The scam lasted for a while, but eventually it caught up with them.

In early 2013, WSEX went out of business.

A few days later, Schillinger was found shot to death in his St. John's condo.

A bullet blew his brains out, a gun lay at his side, a purported suicide note was nearby.

To this day, however, police in Antigua have not ruled the death a suicide--it's still "under investigation," as was originally reported by the San Francisco Examiner in its coverage of the Schillinger death, which can be read at

One thing not under investigation, however, is that Schilinger was a bookie behaving badly, even up to his last minute on Earth.

By Tom Somach

Gambling 911 Staff Writer